If you’re new here, read this quick primer on the Story Energies, a new way to talk about storytelling.

Colin-Corrigan-the-Author is a story. I’ll admit that, as a story, it is not as widely read as, say, Sally-Rooney-the-Author, that “captivating narrative of allure and aloofness, titillation and talent” I explored here back in November, and when the-Author-Colin-Corrigan does finally publish his debut novel, it almost certainly won’t make the same splash as Intermezzo or Normal People or Conversations with Friends.

Almost certainly.

When I first started exploring Substack back in September, the Serious Literary Author (A.K.A. Daniel Piper), was one of the first accounts to catch my attention.

The SLA, I believe, started posting here in July with a series of diary entries, and in the months since he has developed his output to include an Agony Author column and a serialised novel called Secret Agent Luke Warm.

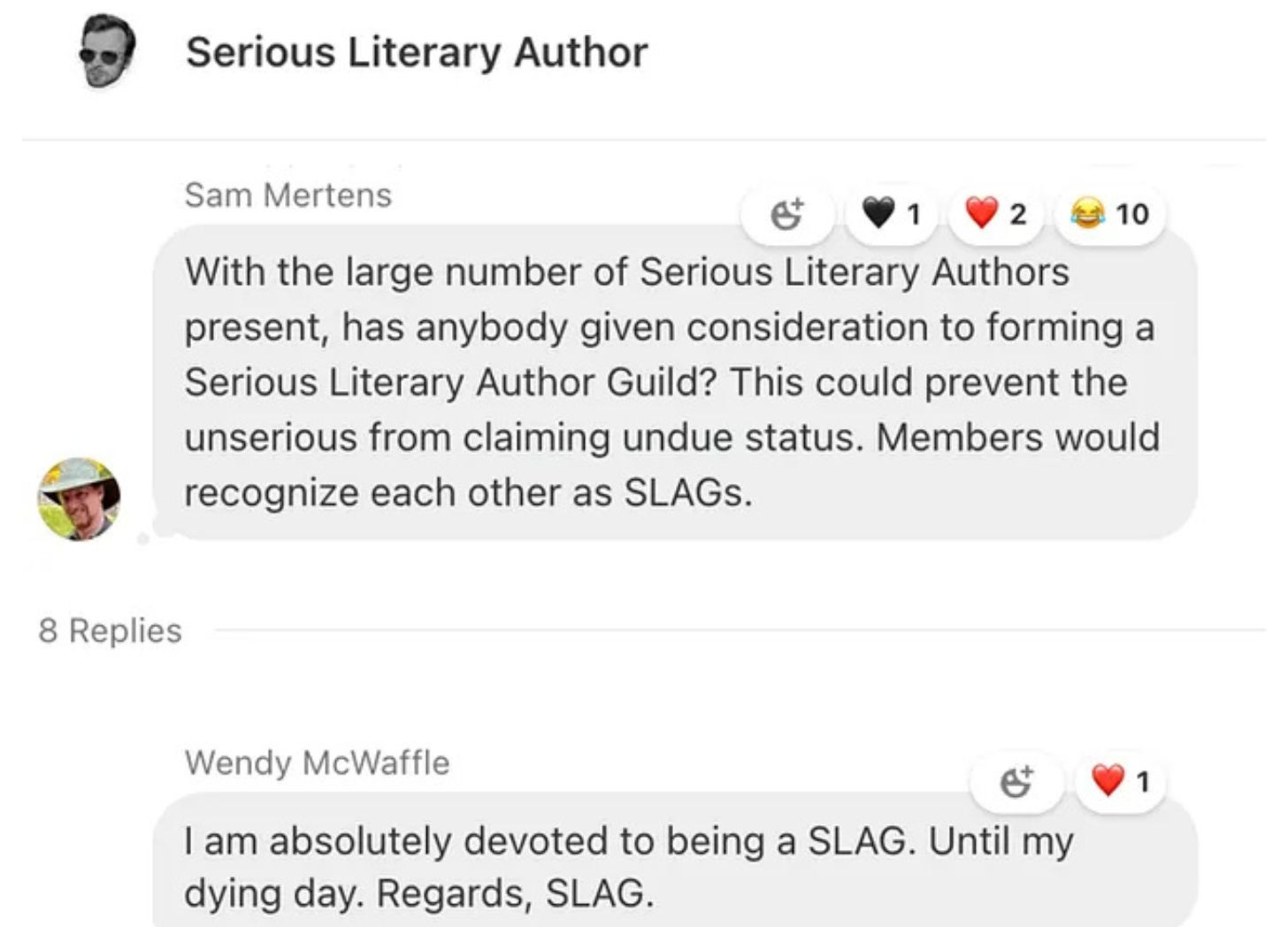

He does not have a million subscribers, but he has amassed an impressive, engaged fanbase, who love chiming in with their own riffs on the theme.

Back in September, I sort of assumed the joke might wear thin after a while, but it turns out there’s a rich seam of material here—the pretensions of authors who take themselves seriously, and of the ‘literary’ work they produce—to be excoriated.

Another Substack writer who keeps making me laugh out loud is Ginny Hogan.

Like the Serious Literary Author, some of her jokes turn their gaze inward…

… but she also looks out at the world. She reads the same news that can make most of us feel sad and unwell, and finds ways to make it funny.

I wouldn’t, for example, have thought to make a joke about restricted access to abortion, nor slavery, but here she was yesterday:

It is not that abortion is funny, of course, nor slavery. The target of the joke is ‘Republicans’, of the firebrand misogynist white-supremacist variety. They are not funny either, generally speaking—they’re really dangerous. But part of us, or part of me anyway, wants to find something to laugh about. And a joke, of course, can be funny and serious at the same time.

One of my favourite serious literary works is the play Rhinoceros, by Eugène Ionesco.

In his youth, Ionesco was bewildered and appalled by the rise of the fascist Iron Guard in his native Romania—their firebrand leader Corneliu Codreanu spouted a kind of Romania First ideology that stoked nationalist sentiment, rejected democratic ideals, and demonised foreigners.

In Rhinoceros, his hapless protagonist Bérenger is bewildered, and then appalled, when his neighbours start turning into rhinos and chasing him off stage. It’s funny and strange and increasingly unsettling [skip to the next paragraph to avoid spoilers!]. Bérenger is not without his own flaws—he’s a drunk, he’s always late; when things get too much for him, he slaps his girlfriend—and when he loses everything, he even tries to turn into a rhino himself. In the end, though, he returns to his senses, and the play, for all its complexities, absurdities and hijinks, conveys a deeply-felt moral argument: we should not all barge around destroying everything.

There is more than one way to be funny.

In our terms, we can generate extreme Elastic Energy, and pop it like a balloon, or a fart.

We can inject a surprise burst of Kinetic Energy when a man is peeing first thing on a morning after.

We can spring back against the forces of Gravitational Energy, and poke fun at our contemporary Manners…

… or the Mysteries of our existence…

… or the mainstreaming of far-right agendas.

Great satire can do all those things, but it finds its real power in the Potential Energy present in its subject.

We’ve talked here before about how a story can gain meaning by giving its characters things they care deeply about (Values), and by making them different from one another and from the rest of humanity (or extreme in some way), and by arming them with a missing limb, or some other sort of absence or lack.

A story can become a joke when its initial, apparent meaning is misconstrued.

This initial meaning can quickly dissipate, like the scarecrow who is outstanding in his field, or the magic tractor that turns into a field, or the two fish in a tank that turn to one another and wonder how to drive this thing.

Other times, the exposed meaning can linger, yawn awfully in our comprehending minds, and keep us awake at night with its stampeding horror.

One thing about Colin Corrigan is that he is serious about literature—he cares about it more than most people, to the extent that he has dedicated most of his life to it, even without widespread acclaim or a huge advance for his debut novel (yet!). When he has two young children who will probably one day want to go to college, and who would prefer not to one day be shackled by the need to financially support their father in his ‘retirement’ from his ‘career’.

Serious Literary Author is funny because it is true—I find it funny because I see myself in his pretensions and failures, and you might find it funny because you also see yourself in him, or because you see people like me in him.

Rhinoceros is funny because those fascist movements of the 20s and 30s really did somehow turn lots and lots of people into abominations who really did commit all sorts of atrocities. And because the potential to get caught up in one of those movements lies deep within all of us, and it can take us by surprise, so that we can start behaving bestially before we even realise it, and then it’s too late.

If you’re looking to write great satire, you need to find those extremities, whether they’re relatively benign or terribly malignant. If you dig really deep, and look very closely at the most atrocious parts of yourself or of those around you, you might find something really worth laughing at. And you might create a piece of literature that is worth taking seriously.

Sometimes, when we read the news, the world can feel so strange. So much more stupid than our worst imaginings. When the tycoon President of the USA can get excited about the real estate opportunities in a war-ravaged Gaza Strip, it can feel like we live in a world beyond the reach of satire.

But these are exactly the moments that demand that our Literature be Serious. This is when a real author, sincere of heart and true of spirit, can step forward and make us laugh. This is how Literature can expose the hypocrisy and emptiness of caustic rhetoric, change the minds and hearts of the people, and save the world.

As Bérenger in Rhinoceros cries: “I'm not capitulating!”

And as the Serious Literary Author declares: It’s not meant to be funny.

For more on Values and how people can be convinced of all sorts of things by the stories they tune in to, read this:

For more on generating Gravitational Energy by harnessing Mysteries and Manners, read this:

For more on generating Potential Energy by opening a vacuum or void with your characters, read this:

Subscribe to Ginny Hogan on Substack here:

Subscribe to the Serious Literary Author here: