If you’re new here, read this quick primer on the Story Energies, a new way to talk about storytelling.

Dear Storytellers,

It’s now been seven weeks since the Story Energies set sail on this sea of Substacks. Already I’ve talked about the Potential locked into The Penguin’s malformed toes1, the Gravity Kamala Harris couldn’t fly clear of2, and the Magnetism in the bonds between sisters (in His Three Daughters3) and brothers (in Intermezzo4). I’ve talked about Standard Storytelling Advice (of the kind inspired by Romeo and Juliet5), and how it doesn’t fit all stories (such as fizzled-out relationships6). And about how we should combine this advice with lessons we’ve learned from our own lives if we hope to compete with AI storybots7.

My emphasis so far has been on Witnessing the Story Energies in action, with some notes on how to incorporate them into your storytelling Process. Today I’m bringing you my first dedicated Harness post, that focuses on one particular form of Energy, and offers more detailed, practical advice for how to add it to your own stories. This post will also include my first paywall, and over the coming weeks I will be adding more content that’s only available to paid subscribers, in the hope that this project will one day become sustainable.

Don’t panic!—I will still be publishing some posts that are free for all, and I have extended the Launch Party! 60-day free trial offer so that you can avail of it right up to Christmas Eve8. If you would like to be a paid subscriber, but can’t afford it, please send me a DM here on Substack9, or an email at colinteacheswriting@gmail.com.

But with no further ado, let’s get down to Gravity.

Whether we’re building a brand-new science-fictional universe where Mars has been colonised by squids, or a piece of observational journalism about a plumber fixing kitchen sinks, we need to present to our audience a world they can believe in.

And the more richly we imagine our story world—the more detailed and specific and vibrant we can make it—the more force it will exert on our audience, to draw them into our story.

Think of stained steel, frayed sealant, bubbled and blistered laminate.

Or smooth ceramic set against sleek granite.

Or a Martian dust storm causing havoc with a saltwater tank’s filtration system.

Plumbing aside, our story worlds really come alive when characters start moving around within them. Observing. Experiencing. Sensory details, things a character can see (a black rubber plunger with a plain wooden handle) and also hear (squelchy sucking splash), feel (sprayed droplets against a wincing grimace), taste (bile, last night’s tequila, last night’s tacos), and smell (oh my), help us beam our imagined worlds into the minds of our readers. Help them experience the story along with our characters.

Which is really important, and absolutely worth bearing in mind.

But my world is more than just a physical reality to be witnessed and reckoned with. My life’s setting is not just my town, my house, my toilet; it’s also my family, my community, my culture, my society. My universe exerts all sorts of forces upon me, and impacts my life in all sorts of ways—the roles I’m expected to play as a dad10 and a husband, the robots that answer my phone calls to my phone company, the new online writing platform that soaks up all my free time, the extreme weather events that drive up my home insurance, the literal gravity that stops me floating away…

I’ve already mentioned Flannery O’Connor here a couple times—the Potential added to her story Good Country People by her ‘lady PhD’’s wooden leg11, and her endorsement of a pantsing approach, via which she arrived at the revelation that her bible salesman would steal that leg a few sentences before she had him steal it12.

And I think one of her most useful pieces of advice is that all fiction (and I think by extension all forms of storytelling) can essentially be reduced to Mystery and Manners—this idea was so important to her, it became the title of her collected essays13.

For O’Connor, Mysteries—those deep essential questions about the meaning of our lives—had a lot to do with her Catholicism. And Manners—the social norms and conventions which characters have to navigate—had a lot to do with the particularities of her culture in the American South. But I think it can be very useful for all of us to consider those categories, Mysteries and Manners, more broadly when imagining the settings of our stories.

Each universe has its Mysteries—its own questions about how things work. These can be answered with something like our laws of physics, or with a more spiritual view of the world where miracles might be reasonably hoped for, or with a new set of natural laws, like in a fantasy or science fiction story, or like when Cinderella’s coach can turn back into a pumpkin at midnight.

And every society has its Manners—the pressures and expectations placed upon its groups and individuals, its complicated roles which people are supposed to play.

Another, perhaps more straightforward way to think about this is to imagine the various rules that exist in the world of your story, which govern how nature and people can or should behave.

But I like using Flannery O’Connor’s terms, Mysteries and Manners, because they’re suggestive not just of concrete rules, but of a more human appreciation of them.

Some Mysteries remain unanswerable, yet are endlessly interesting to consider.

Good manners dictates not just how I should behave, but also what might happen when I break the rules.

Fallout is a novel by Eleanor Anstruther that is being serialised right here on Substack.

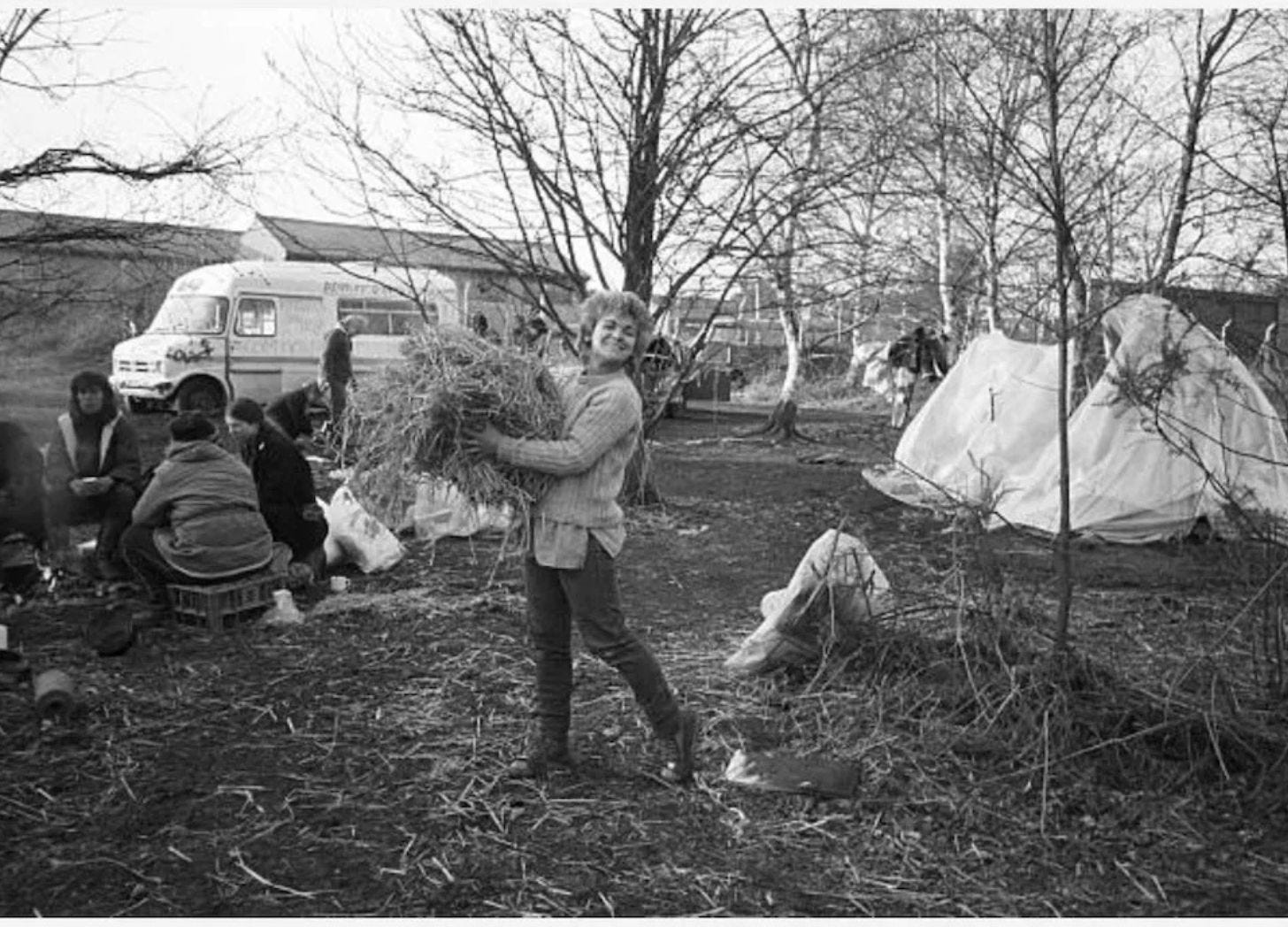

It’s set in 1980s England against the backdrop of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, which was a protest against the deployment of nuclear-armed cruise missiles at an RAF base in Berkshire. These American missiles were part of the Cold War policy of Mutually Assured Destruction—MAD for short—and were considered by some to be an essential deterrent to a Soviet nuclear attack. But others were understandably wary of a nuclear arsenal being installed so near to their houses and kids’ schools, or were more generally anti- nuclear proliferation (/annihilation). The story of the Peace Camp is a remarkable one, which deserved more coverage by the news media at the time, and which warrants more recognition today.

As Anstruther writes in the novel’s introduction:

I thought I knew about Greenham until I began the research. I knew it wasn’t just a story of dirty lesbians washing up at an RAF base in Berkshire in the 1980’s, a women only camp that put men’s backs up, but I was not prepared for stories of heroism, stoicism, comedy, music and art. I didn’t know the Women’s Peace Camp stayed for nineteen years. I didn’t know the British government licensed the army to use live ammunition on them, or of the anecdotal evidence of countless abuses of their human rights, from chemical weapons to sexual violence, vigilante attacks to the universal right to live free of the war plans of others. And I didn’t know that in the peace accord signed between Russia and America, both sides cited Greenham Women as their inspiration.

Her story opens on teenaged Bridget, having breakfast with her family before school, as her attention is piqued less by the leaflet advertising a protest than by the way her mum tries to hide it from her dad. The early chapters follow her as she learns more about the protest at school, and then sneaks off on her first excursion from her London suburb to the base in Newbury.

We then switch perspective to her teacher Annabel who, walking through the protest, feels liberated from the claustrophobia of her regular everyday existence, where she fantasises over the arrival a new teacher with a swathe of tumbling brown hair, but instead has to endure a staffroom filled with ranks of matrons and identikit Lady Dianas.

We then switch again to Bridget’s mum, Janet, who is wrangling her sons and trying to get dinner ready and starting to really worry because her daughter’s still not home…

In a pleasant version of what’s sometimes called kitchen sink realism, this particular time and place are brought vividly to life with all sorts of specific, intimate details. Janet shoves the flyer into her “wide floral front pocket deep with lint and tissues and Rothmans cigarettes and a lighter,” her husband pores over his folding maps, Annabel satisfyingly slices new flyers with the art-room guillotine.

This carefully conjured setting looks and feels authentic, and attracts us readers like an old photograph of someone we almost recognise. But that’s not all it does—it also exerts all sorts of forces upon the characters, and impacts their lives in all sorts of ways.

There are the Mysteries. Big, mostly unspoken questions at the heart of the story, like: How can we bring about peace in a world with so much violence? or: How should we balance our need to save the world with our more immediate responsibilities to our families?

And there’s all sorts of Manners to be navigated. Women are supposed to wear the right make-up and use hairspray correctly, and not have queen-size beds in their rented rooms, and certainly not run off to set up camp in the mud outside an airforce base where there is every chance they will soon get arrested…

By setting her story against a backdrop of such a compelling protest (which itself was set against the threat of nuclear annihilation), and by bringing it so lovingly to life, with such careful attention to detail, Anstruther generates a huge amount of Gravitational Energy, which both draws us readers into the story, and also influences the development of the story itself, as the characters try to navigate the very particular challenges presented to them by this very particular world.

So how can we generate more Gravitational Energy in our own stories?

Look for specific, compelling details that set your setting apart from most other places. These could be to do with clothes, food, tools, toys, furniture, buildings, accents, hairstyles, laws, kitchen sinks, or any of the myriad of things that together constitute a story world.

And consider the Mysteries and Manners of your universe. What big questions are your characters haunted by? What expectations does society have for your characters? And what will happen when your characters fail to meet them?

To discover and explore everything this new approach has to offer, sign up for 60 days of free, full access to all Story Energies content as we get up and running.

To help with this, see below for the first Story Energies Writing Exercise.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Story Energies to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.