If you’re new here, read this quick primer on the Story Energies, a new way to talk about storytelling.

Dear Storytellers,

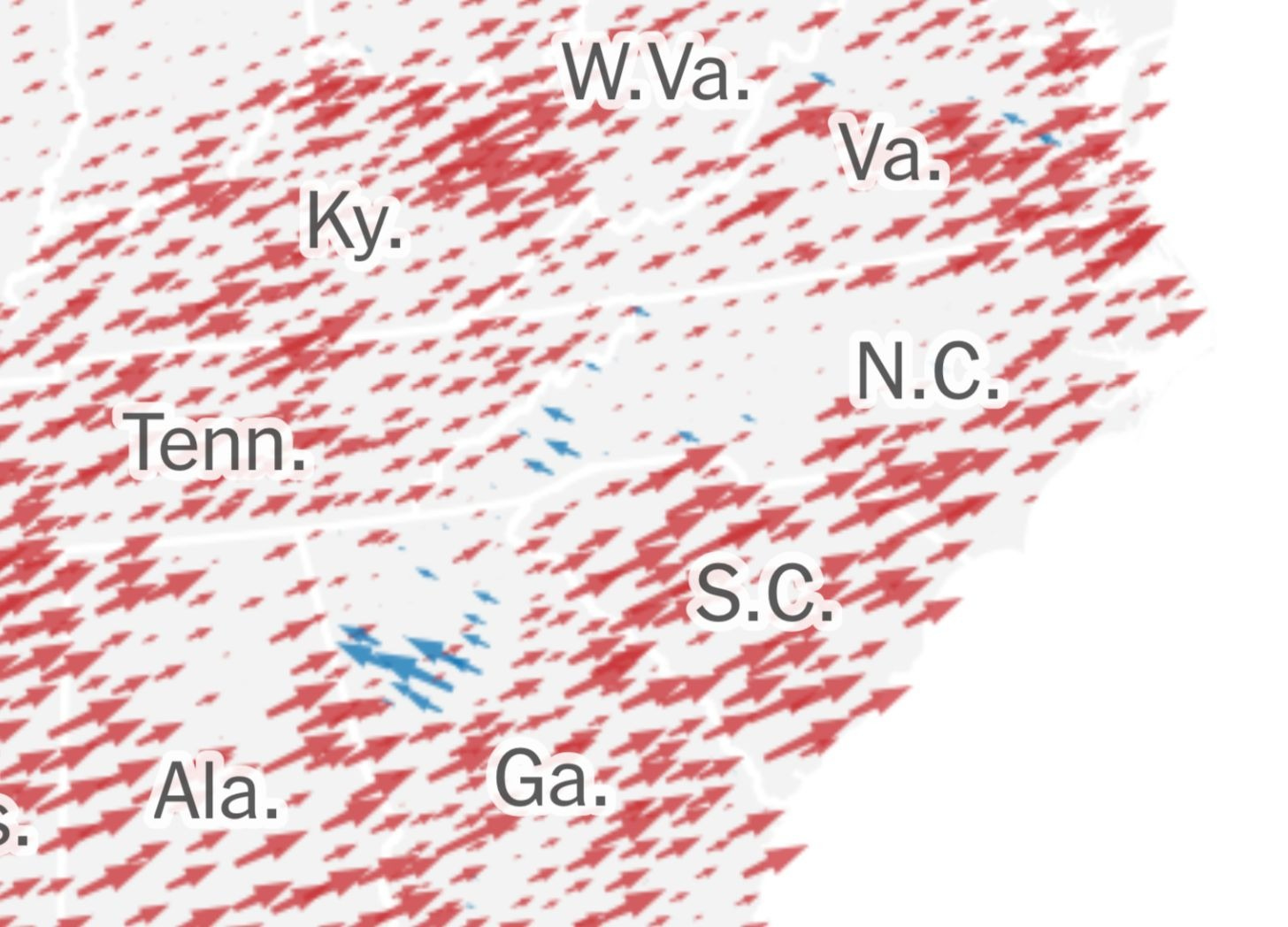

I’m going to start with a quick follow-up to last week’s post, when I looked at the various story energies running through Kamala Harris’s campaign1. In the end, it seems she wasn’t able to overcome her problems with Potential Energy—as a relatively unknown candidate with relatively limited national exposure—and Gravitational Energy—those realities of war, economic hardship, and right-wing scaremongering she needed to spring from.

There’s a lot more I’d like to say about all that, but for now I’m going to leave the politics to the politicos2 and return to the world of fiction. Where, as storytellers, we are in full control of the tales we invent.

Right?

Before I wrote fiction, I wrote screenplays, and these two writing communities, very broadly speaking, have very different approaches to coming up with new stories.

With screenwriting, the emphasis is on structure, and planning out your story before you begin. Write your logline, your synopsis, your outline, then line up a domino chain of twists and turns, from your set-up through your inciting incident and rising action all the way to your climax and resolution—and the scenes will then write themselves (or at least that’s the idea). As the writer, you impose yourself upon your story, and try to dictate its every beat.

But with fiction, particularly short fiction, I encountered a radically different approach: Don’t plan. NEVER PLAN! Plans are creativity cages that limit your story to what you can imagine now, instead of opening it up to everything you can discover in the process of writing it. Instead of Planning, just ‘Pants’ it—write by the seat of your pants, and let the story find its own flow, and fulfil its own destiny. As the writer, your job is to forfeit control of your story to… your characters? Your unconscious? To Story itself? It’s unclear, exactly, how this works, but that’s all part of the miraculous mystery of artistic creation!

Each of these very different approaches—Planning and Pantsing—has its advantages and limitations. If we plan too much, we risk stifling our innovation, even as we reduce the joy of writing to colouring in the blanks. If we don’t plan at all, we can take off boldly exploring and end up utterly lost knee-deep in a shapeless, incoherent mess.

Each of us storytellers has to find our own balance. And it’s hard! Maybe you have already settled on an approach you’re comfortable with, but if you’re like most of us, and you find yourself in one camp—a Planner or a Pantser—you probably worry that you should be doing more of the other.

In my post Phantom Potential3, I wrote about Flannery O’Connor writing about writing her short story Good Country People. She gave her ‘lady PhD’ character a wooden leg, and it rapidly acquired meaning, and when a bible salesman came along, he simply had to steal it. She tells us:

I didn’t know he was going to steal that wooden leg until ten or twelve lines before he did but when I found out that this was what was going to happen, I realized that it was inevitable. This is a story that produces a shock for the reader, and I think one reason for this is that it produced a shock for the writer.

This is how the ‘Pantsing’ approach, or to use a more pleasing term, Discovery Writing, is supposed to work. We make lots of things up, and then they all come together in meaningful ways; we surprise ourselves with our own talent, and earn the awe and respect of our readers.

How exactly can we do this? O’Connor continues:

It might be asked how this kind of control comes about, since it is not entirely conscious. I think the answer to this is what [French Catholic philosopher Jacques] Maritain calls “the habit of art.” It is a fact that fiction writing is something in which the whole personality takes part—the conscious as well as the unconscious mind. Art is the habit of the artist; and habits have to be rooted deep in the whole personality. They have to be cultivated like any other habit, over a long period of time, by experience; and teaching any kind of writing is largely a matter of helping the student develop the habit of art. I think this is more than just a discipline, although it is that; I think it is a way of looking at the created world and of using the senses so as to make them find as much meaning as possible in things.

In your life: look closely at the world, and try to discern meaning.

In your writing: get into the habit of introducing as much potential for meaning, for story, as you can. As early as you can. Identify, to use our term, the Potential Energy in character traits, beliefs, behaviours, settings, objects. Be specific. A wooden leg has more potential than a regular one. A bible salesman offers more to a story than books.

How can we generate that Potential Energy in our own stories? One place to start is to ask how people find meaning in their lives. And one answer to that question is that they find things to care about. It’s really hard not to care about anything for very long—just ask the wannabe-nihilist heroine of Good Country People. And the stronger those feelings are—for a daughter, or a career, or the New England Patriots—the more Potential Energy you have in your story.

Think about the Values in your story. Things a character, or a community, believes in. Cares about. Considers important.

Think too about what a character might think they care about, and what they actually care about.

For example, a character might think that they care about the environment, and slowing climate change. But they might not care about all that as much as they do about, say, being able to fill their gas tank so they can get home from work and kiss their children goodnight.

Unless, for example, their communities have been ransacked by a recent hurricane, and the need to do something about this climate catastrophe has moved from a somewhat abstract question to one that is terrifyingly concrete.

Another character might think that racism is bad, but she might also feel a strong connection to her idea of her country where she and people (who look) like her and her family have pride of place. Another character might see the importance of protecting the institutions of democracy, but also feel that, if stocks soar and taxes are cut, he’ll finally be able to buy that boat.

So I guess I haven’t put the election altogether out of my mind. But for storytellers of all stripes, thinking about Values—the things people believe in—can help you generate more Potential Energy for your story.

And if you can make your characters believe in competing or conflicting values—if one character cares about a woman’s right to abortion, for example, while another really tries to listen to their Catholic priest—then you’re suddenly on the verge of a compelling story. If the same character is genuinely passionate about both a woman’s right to choose and obeying their priest, that could bring even more urgency and agony to your story.

Especially if you can make her a champion of her local chapter of Women for Trump, then get her daughter drunk at a frat party.

If you’re a Planner, it’s pretty easy to harness the Story Energies from the beginning4. Introducing Potential Energy is clearly important, and making sure that your characters have things that they care deeply about is a great place to start. Potential Energy can then be easily converted to other forms of Energy as the story unfolds, perhaps as you take one of those things your character cares about and have another character steal it, or set it on fire, or lock it in a dungeon.

If you’re a Pantser, it’s a bit more difficult, but try to remember your ‘habit of art’. See if you can direct, or even train, your unconscious creativity to make smart choices as it goes. Make your characters active, steer them towards conflict, give them things to care deeply about. And see where they take you.

To discover and explore everything this new approach has to offer, sign up for 60 days of free, full access to all Story Energies content as we get up and running.

You can hear Good Country People read aloud by Steve Wilkins here.

You can purchase O’Connor’s Mysteries & Manners or Complete Stories at Bookshop.org, and support local bookstores.

I recommend, if you don’t already read Heather Cox Richardson, her Letters from an American.

Stay tuned for lots more posts with tips on how to do this.

I'm a bit late to the party on this post, but I love that quote from Flannery O'Connor, especially when she says she had no idea going in that the bible salesman in Good Country People would steal the leg. I was just reading that story in a GrubStreet class two weeks ago. The admission, like her sudden decision, feels mind-blowing yet inevitable.